본격!! 식물 생태와

생물 상호작용

식물의 다양성과 번식 형질은 해발고도가

높아질수록 어떻게 변할까?

기후대와 같이 고도는 생물종의 분포를 결정짓는 깔때기 역할을 한다. 이 때문에 고도에 따른 생물종의 분포와 이들의 적응 양상은 오래전부터 많은 생태학자들의 관심사였다 (Rahbek 1997; Lomolino 2001; Grytnes and Vetaas 2002; Sanders 2002; Oommen and Shanker 2005; Grytnes et al 2006; McCain 2007a,b).

해발고도가 높아질수록 공기의 밀도는 점차 낮아지고 기온 감률에 따라 온도도 감소한다. 강하게 부는 바람, 예측할 수 없는 적설과 폭우, 강한 자외선은 고산 기후 및 기상을 특징짓는 요소들이다. 이러한 극한의 환경에서 동물처럼 피신할 수만 있다면 더할 나위 없겠지만, 식물은 가혹한 기후와 기상 현상들을 온 몸으로 견뎌야 한다. 설악산 꼭대기에 올라서면 우리는 산 아래에서 보던 것과는 다른 특징을 가진 식물종을 볼 수 있다. 가령, 만병초와 같은 식물을 보더라도 크고 화려한 꽃으로 매개자를 유인하고 강한 바람에 견딜 수 있는 두꺼운 잎을 가진다. 이들은 ‘높은 해발고도’라는 생물 깔때기에서 여과된 식물종인 것이다.

우리는 높은 해발고도라는 ‘깔때기’를 통과하여 살아남은 고산식물종의 차별화된 생존방식과 한국 지리산의 고도에 따른 식물 번식 형질의 변화를 간략히 설명하고자 한다.

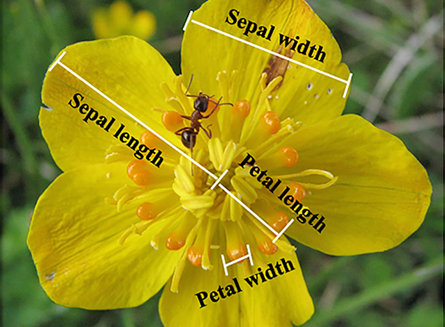

고산지대의 대표적인 꽃의 형태

(Zhao and Wang. 2015. Selection by Pollinators on Floral Traits in

Generalized Trollius ranunculoides (Ranunculaceae) along Altitudinal Gradients.)

우리나라 고산식물종인 만병초와

수분매개자(꼬마꽃벌류)

고산지역에서 피는 꽃들의 비밀

고산지역에서는 방사대칭 형태로 위쪽이 열린 그릇 (bowl) 형태의 꽃이 가장 흔하게 관찰된다. 일반적으로 고도가 높아질수록 수분매개자의 다양성과 풍부는 감소하므로 이곳의 식물은 매개자를 유인하기 어렵다. 이와 같은 조건에서 그릇 모양의 꽃은 곤충과 같은 화분전달자의 접근과 활동이 쉽고, 예측 불가능한 고산의 환경에서 수분 확률을 최대로 끌어올릴 수 있다 (Waser et al. 1996; Rathcke 1988; Olesen and Jordano 2002; Herrera 2005).

그렇다면 어떤 꽃색이 가장 흔할까? Pickering and Stock (2004)은 호주 고산지대 (Mt. Kosciuszko)는 204종 중 127종이 화려한 색의 꽃을 가지고 있으며, 흰색 꽃이 절반 이상을 차지함을 밝혔다 (흰색: 53.5%, 노란색: 21.3%, 분홍색-붉은색: 11.0%, 파란색-보라색: 4.0%). 반면에 Peng (2012)의 중국 고산지대 (Mt. Hengduan) 연구에서는 파란색-보라색 (42.7%), 노란색 (29.6%), 흰색 (18.1%), 분홍색-붉은색 (9.4%) 순으로 크기가 크고 밝은 색상을 가진 꽃들의 나타났고, Nakano and Washitani (2003)와 Gong and Huang (2011)의 연구 역시 고산지대 초지에서 파란색-보라색 꽃의 비율이 높은 것으로 나타났다. 이 연구들로부터, 꽃색은 단순히 해발고도라는 물리적 환경에 의해서만 결정되는 것이 아님을 알 수 있다. 따라서 꽃색의 결정에는 군집 내 매개자상(pollinator fauna), 식물-수분매개자 상호작용, 종 간 경쟁과 같은 복잡 다양한 생물적 요인이 작용했을 가능성이 더 높을 것이다 (Schemske and Bradshaw 1999; Koski and Ashman 2015).

고산식물은 가혹한 환경에서 수분 기회를 높이기 위해 개화가 비교적 오래 지속되는 특성을 가진다 (Fabbro and Körner 2004; Arroyo et al. 2006). 고산지역의 날씨는 변덕스럽다. 특히, 봄철에는 예상치 못한 적설로 인해 피었던 꽃이 눈에 묻힐 수 있고, 저온 및 강풍으로 인해 매개자의 활동이 저하되므로 수분 확률이 현저히 낮아질 수 있다. 이를 보상하고자 많은 고산 식물의 꽃은 천천히 그리고 오랫동안 피는 특성을 지닌다 (Bingham and Orthner 1998).

고도에 따른 번식특성 변화는 군집 속성을 바꾼다

식물 번식 생태학 (plant reproductive ecology)의 오랜 역사에도 불구하고 고도에 따른식물의 성체제 (sexual system)와 교배체제 (breeding system)의 변화 양상에 대한 정보는 상대적으로 부족하다. 해발고도가 높아질수록 식물의 자가수분(self-pollination) 비율은 증가하며 (García-Camacho and Totland 2009; Körner and Paulsen 2009), 가혹한 조건에서 쉽게 번식이 가능한 양성화의 비율이 높아진다. 또한 수분전략과 관련하여 고산식물 중 풍매와 충매같은 단일 매개체에 의존한 수분보다 바람과 동물을 복합적으로 이용하는 종들 (ambophilous)의 비율이 증가한다. 이 같은 양상은 고산지역의 가혹한 환경에서 수분기회를 증가시키기 위한 식물의 번식 전략을 보여준다. 예를 들면, 파타고니아에서 해발고도에 따라 단성화 종은 상대적으로 비율이 감소한다 (Arroyo and Squeo, 1990). 다른 연구 (Vamosi and Queenborough, 2010) 에서는 고산식물의 양성화 꽃은 강제 이종교배(obligate outcrossers)와 다수의 곤충 방문자들에 의존하기 때문에 양성화 꽃 발생은 곤충들의 다양성, 풍부도 및 활동성 등의 감소로 인해 해발고도가 증가함에 따라 증가한다고 밝혔다.

한편, 최근 연구들은 군집-생태학적 맥락에서 꽃의 특성을 고려한 연구 (Benadi et al. 2014; Junker et al. 2013; Runquist et al. 2016; Wolowski et al. 2017)가 진행되며, 이러한 특성이 식물군집 구성에 기여한다고 밝혔다 (Benadi 2015; Pauw 2013; Sargent and Ackerly 2007). 실제로, 형태학, 색상, 향기 및 모양 등의 꽃 특성은 식물-매개자의 상호 작용 결과로 궁극적으로 군집 내 매개자 다양성과 식물 간 수분 경쟁에 영향을 미친다 (Carvalheiro et al. 2014; Junker et al. 2013, 2015; Junker and Parachnowitsch 2015; Kuppler et al. 2016; Larue et al. 2016). 게다가 꽃과 수분특성은 식물의 번식 및 적합도 (fitness)와 직접적인 영향을 준다. 이는 곧 식물 군집의 생물량과 종 다양성의 뼈대를 이룬다. 따라서 식물의 꽃과 수분특성은 군집의 형성과정을 살펴볼 수 있는 중요한 단서가 된다. 더 나아가 해발고도에 따른 식물의 꽃과 수분특성의 적응 양상은 결국 고도에 따른 식물 군집의 변화를 예측하는데 필수적인 정보가 될 수 있다.

해발고도에 따른 지리산 서식 식물의 다양성 변화 양상

전 세계적으로 해발고도에 따른 식물 다양성 변화 양상에 대한 많은 연구가 진행되었다.

가장 대표적인 연구로 Rahbek (1995, 2005)은 해발고도에 따라 종 풍부도의 패턴은 해발고도가 증가함에 따라 단조롭게 감소하거나 해발고도의 중간지점에서 최대 종 풍부도를 나타내는 역 u자형(hump shaped)의 두개의 주요한 패턴을 밝혔다. 또한 현재까지 수행된 대부분의 연구들은 역 u자형 패턴을 이야기하고 있다.

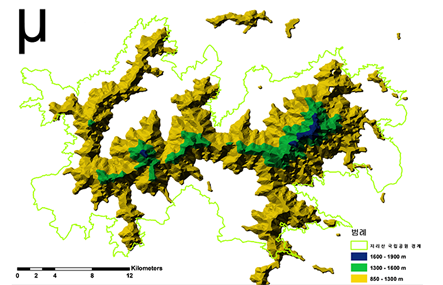

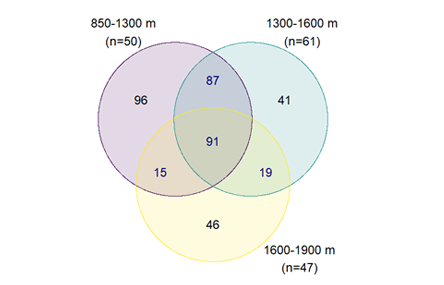

우리는 한국 남부의 가장 높은 지리산에서 앞서 설명한 환경적인 차이를 가진 해발고도를 일정 간격으로 구분하고 (구간 I 850 – 1,300 m, 구간 II 1,300 – 1,600 m, 그리고 구간 III 1,600 – 1,900 m), 이에 따른 식물종들의 번식 형질 분포와 변화 양상을 살펴보았다. 총 70과 175속 269종 4아종 29변종 5품종 307분류군의 식물이 관찰되었으며, 해발고도의 증가에 따라 289종, 238종, 그리고 171종으로 식물 다양성이 감소하는 것을 알 수 있었다. 세 구간에서 모두 출현한 식물은 91 종으로서 전체 출현종의 35 %를 차지하였다. 개별 구간에만 출현하는 식물종을 살펴보면, 구간 I은 96종, 구간 II는 41종, 구간 III은 46종이 출현하여 해발고도 증가에 따라 역시 감소하는 경향이 관찰되었다. 특히, 구간 I과 II 사이의 종 풍부도는 큰 폭으로 감소하였다

해발고도에 따른 성체제, 꽃가루 전달자 (pollen vector), 꽃색의 변화

관찰된 식물종에서 현화식물 260분류군에 대하여, 해발고도에 따른 다양성, 성체제, 꽃가루 전달자, 그리고 꽃색에서 흥미로운 변화를 관찰할 수 있었다.

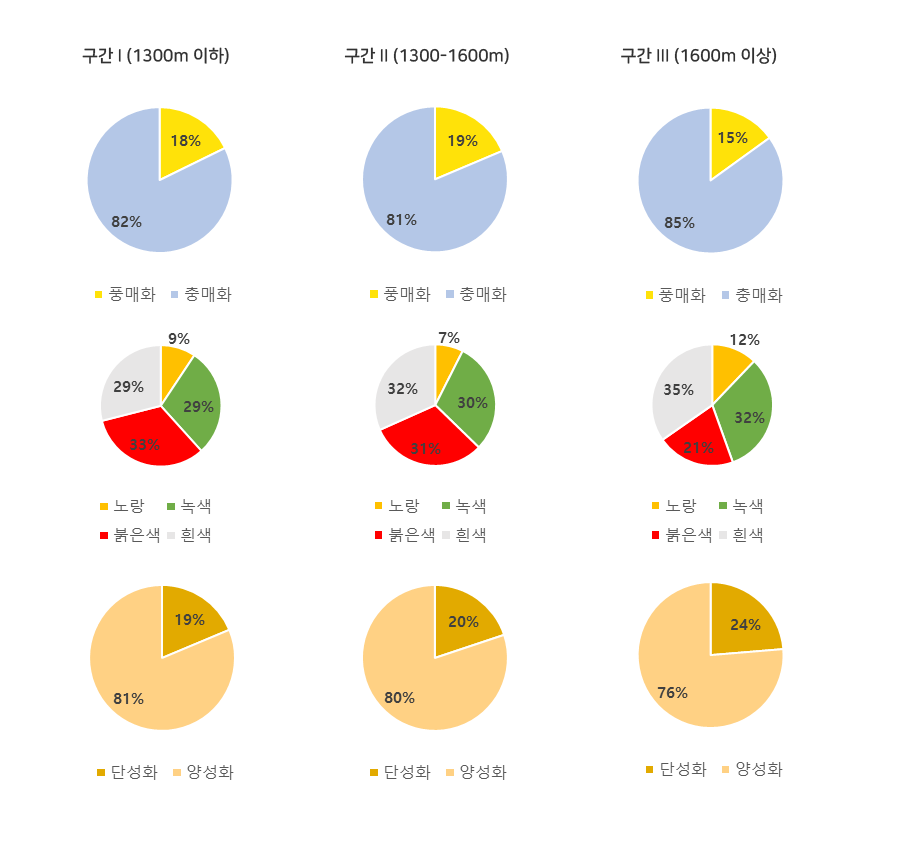

현화식물의 다양성은 전체 식물다양성 감소 경향과 동일한 크게 감소하는 봉우리 모양을 나타냈다; 구간 I 173종, 구간 II 161종, 그리고 구간 III 107종. 식물군집 내 구성종의 성체계에서, 단성화 및 양성화의 다양성은 종다양성의 감소하는 경향과 동일하였다. 그러나 성체제 구성 비율에서 양성화 (구간 I 76.3 %, 구간 II 80.1 %, 그리고 구간 III 81.3 %)는 증가하는 양상이었다.

해발고도에 따른 수분 기작에서 풍매화의 다양성은 증가 후 감소, 그리고 충매화의 다양성은 감소하였다. 식물군집 내 풍매화의 구성 비율은 그것의 다양성과 다르게 감소 후 약간 증가하였고, 충매화에서는 다양성과 달리 감소 (구간 I 85.0 %, 구간 II 81.4 %, 그리고 구간 III 82.2 %)하는 경향이었다.

꽃색에서 식물종 다양성은 노랑, 녹색, 그리고 흰색은 감소, 그러나 붉은색은 증가하는 경향이었으며, 군집 내 구성 비율은 노랑은 감소 후 증가, 녹색과 흰색은 거의 변화가 없었으며, 붉은색은 크게 증가하는 다양한 양상을 나타내었다.

우리가 관찰한 지역에서 현화식물의 특성에 따른 다양성은 해발고도가 높아짐에 따라 양성화 비율이 증가하고 보라색을 포함한 붉은색 계열의 꽃색이 증가하며, 풍매화의 수분 기작을 가진 식물종에 비율이 증가하는 것으로 나타났다. 또한 비교적 고해발 지역인 우리의 관찰 범위에서 양성화는 항상 높은 구성 비율 (76.3 %에서 81.3 %까지)을 차지하고 있었다. 식물 다양성 변화와 그들이 가지고 있는 특성 변화는 다른 변곡점을 가지고 있었다. 식물 다양성 변화는 구간 I과 II에서 급격하게 변화되었으며, 그들이 가지고 있는 특성의 변화는 구간 II와 III에 두드러지게 나타났다. 우리나라에서도 해발고도에 따라 적응한 식물 종들의 다양성과 그 특징이 유사한 경향을 나타냈다.

우리가 분석한 지리산 고해발 지역의 일부 자료를 살펴본 바, 다양한 국외 연구들과 유사한 패턴을 보였지만 상세한 현장 조사가 추가적으로 필요하다. 해발고도를 비롯하여 숲의 나이, 토양 성숙도, 강수량, 연평균 기온, 그리고 위도와 같은 다양한 환경 경사는 다양한 공간 규모에서 한국의 식물종 분포와 형질 변이에 영향을 주고 있다. 관련한 내용에 대한 다양한 접근들이 수행된다면 한반도에서 식물 다양성이 공간 양상, 그리고 구조화되는 기제를 이해하는데 도움이 될 것이다

<참고문헌>

Arroyo MTK, Mun˜oz MS, Henrı´quez C, Till-Bottraud I, Pe´rez F. 2006. Erratic pollination, high selfing levels and their correlates and consequences in an altitudinally widespread above-tree-line species in the high Andes of Chile. Acta Oecologia 30:248–257.

Benadi G, Hovestadt T, Poethke HJ, Bluthgen N. 2014. Specialization and phenological synchrony of plant–pollinator interactions along an altitudinal gradient. J Anim Ecol 83:639–650.

Benadi G. 2015. Requirements for plant coexistence through pollination niche partitioning. P R Soc B 282:Artn 20150117.

Bingham RA, Orthner AR. 1998. Efficient pollination of alpine plants. Nature 391:238–239.

Carsten Rahbek, 1997. The Relationship among Area, Elevation, and Regional Species Richness in Neotropical Birds, The American Naturalist 149, no. 5, 875-902.

Carvalheiro L et al. 2014. The potential for indirect effects between co-flowering plants via shared pollinators depends on resource abundance, accessibility and relatedness. Ecol Lett 17:1389–1399.

Fabbro T, Ko¨rner C. 2004. Altitudinal differences in flower traits and reproductive allocation. Flora 199:70–81.

Garcı´a-Camacho R, Totland Ø. 2009. Pollen limitation in the alpine: a meta-analysis. Arct Antarct Alp Res 41:103–111.

Grytnes, J.A., Heegaard, E. & Ihlen, P.G. 2006. Species richness of vascular plants, bryophytes, and lichens along an altitudinal gradient in western Norway. Acta Oecologica, 29, 241–246.

Gong YB, Huang SQ. 2011. Temporal stability of pollinator preference in an alpine plant community and its implications for the evolution of floral traits. Oecologia 166:671–680.

Herrera, C. M. 2002. Censusing natural microgametophyte populations: Variable spatial mosaics and extreme fi ne-graininess in winter-flowering Helleborus foetidus(Ranunculaceae). American Journal of Botany 89: 1570– 1578.

Junker RR, Bluthgen N, Brehm T, Binkenstein J, Paulus J, Schaefer HM, Stang M. 2013. Specialization on traits as basis for the niche-breadth of flower visitors and as structuring mechanism of ecological networks. Funct Ecol 27:329–341.

Junker RR, Bluthgen N, Keller A. 2015. Functional and phylogenetic diversity of plant communities differently affect the structure of flower–visitor interactions and reveal convergences in floral traits. Evol Ecol 29:437–450.

Junker RR, Parachnowitsch AL. 2015. Working towards a holistic view on flower traits—how floral scents mediate plant–animal interactions in concert with other floral characters. J Indian Inst Sci 95:44–67.

Kuppler J, Hofers M, Wiesmann L, Junker RR. 2016. Time-invariant differences between plant individuals in interactions with arthropods correlate with intraspecific variation in plant phenology, morphology and floral scent. New Phytol 210:1357–1368.

Koski MH, Ashman TL. 2016. Reproductive character displacement and environmental filtering shape floral variation between sympatric sister taxa. Evolution 70:2616-2622.

Ko¨rner C, Paulsen J. 2009. Exploring and explaining mountain biodiversity. In: Spehn EM, Ko¨rner C (eds) Data mining for global trends in mountain biodiversity. CRC Press, Florida, pp 1–10.

Larue AAC, Raguso RA, Junker RR. 2016. Experimental manipulation of floral scent bouquets restructures flower-visitor networks in the field. J Anim Ecol 85:396–408.

Lomolino, M.V., 2001. Elevational gradients of species-density: historical and prospective views. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 10, 3–13.

McCain CM (2007a) Area and mammalian elevational diversity. Ecology 88: 76–86.

McCain CM (2007b) Could temperature and water availability drive elevational species richness? A global case study for bats. Global Ecology and Biogeography 16: 1–13.

Nakano C, Washitani I. 2003. Variability and specialization of plant-pollinator systems in a northern maritime grassland. Ecol Res 18:221–246.

Oommen MA, Shanker K. 2005. Elevational species richness patterns emerge from multiple local mechanisms in Himalayan woody plants. Ecology. 86: 3039–3047.

Olesen, JM & Jordano, P. 2002. Geographic patterns in plant–pollinator mutualistic networks. Ecology, 83, 2416-24.

Pauw A. 2013. Can pollination niches facilitate plant coexistence? Trends Ecol Evol 28:30–37.

Peng D‐L, Zhang Z‐Q, Xu B, Li Z‐M, Sun H. 2012. Patterns of flower morphology and sexual systems in the subnival belt of the Hengduan Mountains, SW China. Alpine Botany 122: 65–73.

Pickering CM, Stock M. 2004. Insect colour preference compared to flower colours in the Australian Alps. Nord J Bot 23:217–223.

Rahbek, C., & Museum, Z. 1995. The elevational gradient of species richness: A uniform pattern? Ecography 18, 200–205.

Rahbek C. 2005. The role of spatial scale and the perception of large-scale species-richness patterns. Ecol Lett 8(2):224–239.

Rathcke, B., 1988. Flowering phenologies in a shrub community: competition and constraints. Journal of Ecology 76, 975–994.

Runquist RB, Grossenbacher D, Porter S, Kay K, Smith J. 2016. Pollinator-mediated assemblage processes in California wildflowers. J Evol Biol 29:1045–1058.

Sanders, N. J. 2002. Elevational gradients in ant species richness: area, geometry, and Rapoport’s rule. Ecography 25, 25–32.

Sargent RD, Ackerly DD. 2007. Plant–pollinator interactions and the assembly of plant communities. Trends Ecol Evol 23:123–130.

Schemske DW, Bradshaw HD. 1999. Pollinator preference and the evolution of floral traits in monkeyflowers (Mimulus). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96:11910-11915.

Vamosi SM, Queenborough SA. 2010. Breeding systems and phylogenetic diversity of seed plants along a large-scale elevational gradient. J Biogeogr 37:465–476.

Vetaas, O.R. & Grytnes, J.A. 2002. Distribution of vascular plants species richness and endemic richness along the Himalayan elevation gradient in Nepal. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 11,291-301.

Waser NM, Chiitka L, Price MV, Williams NM and Ollerton J. 1996. Generalization in pollination systems and why it matters. Ecology 77: 1043–1060.

Wolowski M, Carvalheiro LG, Freitas L. 2017. Influence of plant-pollinator interactions on the assembly of plant and hummingbird communities. J Ecol 105:332–344.

Zhao, Z., Wang, Y., 2015. Selection by pollinators on floral traits in generalized Trollius ranunculoides (Ranunculaceae) along altitudinal gradients. PLoS One 10 (2), e0118299.

광릉숲보전센터

임업연구사 조용찬 석사후연구원 김한결 박사후연구원 이학봉